To Chairman Wilson, Vice Chair Hackett, Ranking Member Smith, and members of the Senate Financial Institutions & Technology Committee, thank you for this opportunity to provide opponent testimony on Senate Bill 212.

As this committee knows, SB 212 is a bill requiring people, including adults, to have their age verified before they can legally access (or are denied access to) constitutionally protected speech online when that content is considered

“harmful to juveniles” under current Ohio law.

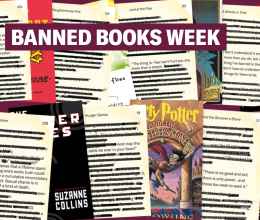

While previous hearings on SB 212 have focused exclusively on pornography, please be aware SB 212 applies to far more speech than what is often or is commonly defined as “pornography”. Indeed, harmful to juveniles laws have been used in the past (and present) to target movies, books, music, comic books, and more. There should be no surprise if and when SB 212 is used the same way.

Because of their subjective nature, such laws have long been a thorn in the side of free speech advocates. Ask 10 (or 25, 50, or 100) people how to determine what is “patently offensive to prevailing standards in the adult community” or if the speech or content “lacks serious literary, artistic, political, and scientific value for juveniles” then prepare to receive 10, 25, 50, or 100 different answers occupying a sliding scale of what these terms mean or should mean.

In addition, courts have long been very protective of free speech rights when government imposes any burdens on adults’ ability to access constitutionally protected speech, including online content. This is especially true when less

restrictive means to accomplish the same goals exist. That is why laws like the type proposed via SB 212 have repeatedly been rejected by federal and state courts over many decades. In short, courts are largely hostile to the idea adults must jump through any government-imposed hoops to access speech and content protected by the First Amendment.

Because of the murky nature of harmful to juveniles laws, many of those who provide content will stop or severely curtail what they make available should SB 212 pass. Some may cease operations altogether. This is because they will

fear prosecution and possible conviction for violations.

The ACLU of Ohio believes such chilling of speech is the intention of many proponents of bills like SB 212. If such bills or laws scare providers into leaving the state or diluting content to only that which is acceptable to, say, 8-year-olds, then many proponents still accomplish their ultimate and publicly stated goal of restricting or ending access to pornography (and/or other content) for both adults and children.

Of course, other means are available for parents to restrict access by their children to questionable materials by their children without any government involvement. Software exists to block access to individual websites. Filters can be used to restrict access to sites with particular words, images, or content. Other methods can be used to track online activity and learn what was accessed. Such tools are more widely available than ever before, at low prices, many times entirely free. Because parents, not the government, may or do make such decisions and utilize such tools, First Amendment rights are not implicated.

On a related note, SB 212 can be subverted through the use of a virtual private network, or VPN. Such a service allows people to use and surf the internet in anonymity. Like the blocking and filtering software just mentioned, VPN technology is prevalent and inexpensive, some of it free. This reality may very well make bills such as SB 212 moot in a practical, if not legal, sense.

Members of this committee, there are other reasons to oppose SB 212. But, my intention for now is to raise concerns about the constitutionality of SB 212, how the goals of many proponents can be accomplished without government action, and why SB 212 may ultimately have little impact on minors’ ability to access pornography and other content. The ACLU of Ohio encourages your rejection of Senate Bill 212.