While President Trump’s executive order against immigrants from six predominantly Muslim countries is in the courts, it is worthwhile to remind ourselves that the stated reasons for immigration reform—protecting against terrorism from the Middle East—are not supported by the facts.

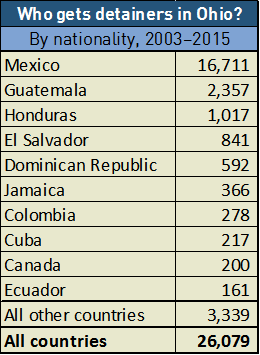

Using Syracuse University’s TRAC Immigration database, I analyzed how immigration detainers were used in Ohio from November 2002 through September 2015. During these 13 years, more than half of the 26,000 detainers in Ohio were placed on citizens of Mexico. Citizens of other Spanish-speaking countries accounted for most of the other detainers.

A tiny minority (0.6%) of detainers were placed against immigrants from the six countries listed in the latest executive orders, and few of these detainers were used against serious criminals or security threats. Of 161 detainers issued against citizens of Syria, Iran, Libya, Somalia, Sudan and Yemen, the government took custody for deportation of only 39. Non-violent drug offenses were the most common violation. No murder or manslaughter convictions existed, but one immigrant from these countries had been convicted of rape. Other convictions included assaults, robberies and a kidnapping. Most disturbingly, over half had no criminal conviction at all.

The problem with detainers is how automatically and broadly they are applied. Any contact with law enforcement can throw a person and family into a cycle of destruction where they are short on rights, recourse or proportionality. In an era of over-criminalization, “contact with police” is a poor proxy for whether a person is dangerous or deserving of deportation.

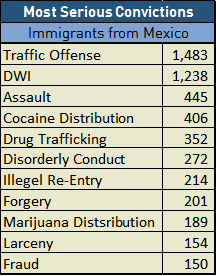

The use of detainers against Mexicans in Ohio tells the same story. Consider:

- Half of Mexicans subject to detainers had no criminal conviction whatsoever.

- The most common conviction: traffic offense.

- The second most common: drunk driving.

Outnumbering every conviction were drug offenses as a whole—2,005 convictions combined. The number shows how the racial nature of the drug war harms minorities in more ways than most people realize.

This indiscriminate use of deportation illustrates the need for “sanctuary city” policies, which are a way to prevent any interaction with local government, especially law enforcement, from escalating beyond what is fair and appropriate. A traffic ticket, a call to 911, a subpoena to testify in court—none of these should automatically trigger a deportation.

Anti-immigrant hardliners want to distort how immigrants are viewed, to make the public think public safety will be jeopardized if constitutional rights are respected. Ohio detainer data shows those claims are false. The president and anti-immigrant blowhards pretend immigration violations are so serious that normal constitutional restraints do not apply—in essence, that the state is free to ignore basic human rights, destroy families because of a civil violation, and treat non-citizens as a kind of legal lower caste. Nonsense.

In truth, nearly all immigrants—even those subject to U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement detainers to be held in prison for possible deportation—are peaceful, hard-working people. A traffic violation, for example, should not put a parent at risk of deportation or leave a child fatherless and a family without income.

Cincinnati, Columbus and every municipality in the country has constitutional authority to become a “sanctuary city.” I explain here how the constitution legally protects the right of my hometown of Granville, Ohio, to become a sanctuary city. (It hasn’t.)

Sanctuary city policies are local efforts to expand constitutional protections to people who need it. The movement reminds me of Ohio’s refusal to enforce federal fugitive slave laws. Constitutional rights matter most when a person comes in contact with police. If the federal government will not respect rights, states and cities must take up the slack, offering constitutional sanctuary to those in need.